Ordering our soul through dialectic and dialogue

Part two of a conversation with DeepSeek (updated February 2, 2025)

A major shared theme between the philosophy of Plato and Stoicism is the idea that we as human beings can achieve harmonious consistency in all that we want and desire so that we never experience internal conflict and never experience frustrated desires. In both philosophies this state is reached by aligning ourselves to objective facts about what is best for human beings. In the philosophy of Plato this is portrayed in several dialogues as the souls journey toward the Good. In the first part of this conversation DeepSeek summarized this:

“While the Republic provides a framework for the rational ordering of the soul, the Symposium and Phaedrus remind us that this ordering is ultimately grounded in love. Together, these dialogues present an integrated vision of the soul’s journey toward the Good, one that balances reason and emotion, order and desire, philosophy and love”.

And that is where we pick up the conversation in this second part:

Jannik: And Socratic dialogue is part of this integrated vision of the soul's journey toward the Good?

DeepSeek: Absolutely! Socratic dialogue is not just a method of inquiry for Plato; it is an essential part of the soul’s journey toward the Good. It embodies the integration of reason, love, and community in the pursuit of wisdom and virtue. Let’s explore how Socratic dialogue fits into this integrated vision:

1. Dialogue as a Reflection of the Soul’s Structure

The tripartite soul (reason, spirit, and appetite) mirrors the structure of Socratic dialogue:

Reason: The dialectical process, driven by questioning and logical analysis, reflects the rational part of the soul. It seeks clarity, coherence, and truth.

Spirit (thumos): The spirited part of the soul is reflected in the passion and commitment of the interlocutors, who often engage in dialogue with a sense of purpose and moral urgency.

Appetite: The appetitive part of the soul is present in the desires and motivations of the participants, who may seek honor, recognition, or personal growth through dialogue.

Socratic dialogue, like the soul, requires the harmonious interaction of these elements. Reason guides the inquiry, spirit fuels the engagement, and appetite provides the underlying motivation to seek truth and understanding.

2. Dialogue as an Expression of Love (Eros)

Socratic dialogue is deeply connected to the Platonic concept of love (eros). In the Symposium, Socrates describes philosophy as the highest form of love, a desire for wisdom and the Good. Dialogue is the medium through which this love is expressed and cultivated:

Love of Wisdom: Socratic dialogue is driven by a shared love of wisdom (philosophia). The participants are united in their desire to understand the truth and to grow closer to the Good.

Love of the Interlocutor: Socrates often expresses care for his interlocutors, even as he challenges their beliefs. This reflects the idea that love is not merely an abstract desire but a relational force that binds individuals together in the pursuit of the Good.

Erotic Ascent: Just as Diotima’s ladder of love in the Symposium describes the soul’s ascent from the love of particular beautiful things to the love of Beauty itself, Socratic dialogue guides the soul from partial, confused understandings to a clearer vision of the Good.

3. Dialogue as a Practice of Recollection

In the Meno and the Phaedrus, Plato suggests that learning is a process of recollection (anamnesis), in which the soul remembers the Forms it once beheld before birth. Socratic dialogue facilitates this process:

Provoking Recollection: Through questioning, Socrates helps his interlocutors “recollect” truths they already possess but have forgotten. This mirrors the soul’s journey toward the Good, which involves recovering its innate knowledge of the Forms.

Midwifery of the Soul: Socrates describes himself as a “midwife” of ideas (Theaetetus, 150b), helping others give birth to their own understanding. This metaphor highlights the collaborative and generative nature of dialogue, which nurtures the soul’s growth.

4. Dialogue as a Path to Self-Knowledge

Socratic dialogue is fundamentally about self-knowledge, which is central to the soul’s journey toward the Good:

Examining One’s Life: Socrates famously declares that “the unexamined life is not worth living” (Apology, 38a). Dialogue is a tool for self-examination, helping individuals understand their own beliefs, desires, and motivations.

Exposing Ignorance: By revealing the limits of his interlocutors’ knowledge, Socrates encourages humility and openness to learning. This is a crucial step in the soul’s ascent, as it requires recognizing one’s own imperfections and striving for improvement.

5. Dialogue as a Communal Activity

The soul’s journey toward the Good is not a solitary endeavor but a communal one. Socratic dialogue reflects this:

Shared Inquiry: Dialogue is a collaborative process in which participants work together to uncover the truth. This mirrors the idea that the Good is a shared goal, attainable only through mutual effort and understanding.

Building Virtue in Community: Just as the Republic emphasizes the importance of a just city for the cultivation of individual virtue, Socratic dialogue creates a microcosm of the ideal community, where individuals support and challenge one another in the pursuit of wisdom.

6. Dialogue as an Embodiment of the Good

Ultimately, Socratic dialogue is not just a means to the Good; it is an embodiment of the Good itself:

Living in Truth: Dialogue is a practice of living in accordance with truth and virtue. It reflects the harmony and order of the Good, both in the individual soul and in the community.

Philosophical Friendship: The bonds formed through dialogue reflect the highest form of friendship (philia), which is based on a shared love of the Good. This friendship is a foretaste of the unity and harmony that the soul seeks in its journey toward the Good.

Conclusion: Dialogue as the Soul’s Journey

Socratic dialogue is an integral part of Plato’s vision of the soul’s journey toward the Good. It combines reason, love, and community in a dynamic process of inquiry, self-discovery, and growth. Through dialogue, the soul not only seeks the Good but also begins to embody it, achieving a harmony that reflects the order of the cosmos and the perfection of the Forms. In this way, dialogue is not just a method of philosophy but a way of life, a practice that brings the soul closer to the Good and to its own fulfillment.

Jannik: Your point no. 6 seems to express the essence of Kenneth Seeskin's book "Dialogue and Discovery".

DeepSeek: Yes, you’re absolutely right! My point about Socratic dialogue as an embodiment of the Good and a way of life aligns closely with the central themes of Kenneth Seeskin’s Dialogue and Discovery: A Study in Socratic Method. Seeskin’s work is a profound exploration of how Socratic dialogue functions not just as a method of inquiry but as a transformative practice that embodies the philosophical pursuit of truth and virtue. Let’s delve into how Seeskin’s ideas resonate with the points I’ve made:

1. Dialogue as a Way of Life

Seeskin emphasizes that Socratic dialogue is not merely a tool for discovering truths but a way of living philosophically. For Socrates, the practice of dialogue is inseparable from the pursuit of the Good. It reflects a commitment to self-examination, intellectual humility, and the continual striving for wisdom. This aligns with my point that dialogue is an embodiment of the Good, as it enacts the virtues (like courage, honesty, and openness) that the Good inspires.

2. Dialogue as a Moral Practice

Seeskin argues that Socratic dialogue is inherently moral because it requires participants to engage with honesty, integrity, and a willingness to question their own beliefs. The process of dialogue cultivates virtues such as intellectual humility, patience, and respect for others. This mirrors my observation that dialogue is not just about reaching conclusions but about living in truth and fostering a community of shared inquiry.

3. The Role of Ignorance

A key theme in Seeskin’s book is Socrates’ famous claim to know nothing. This acknowledgment of ignorance is not a defeat but a starting point for genuine inquiry. Seeskin shows how Socrates uses his professed ignorance to create a space for dialogue, where participants can collaboratively explore ideas without the pretension of having all the answers. This resonates with my point about dialogue as a practice of self-knowledge and humility, which are essential for the soul’s journey toward the Good.

4. Dialogue as Discovery

Seeskin highlights the discovery-oriented nature of Socratic dialogue. Unlike debates, which aim to win arguments, Socratic dialogues are open-ended and exploratory. They are driven by a shared desire to uncover truth rather than to impose it. This aligns with my emphasis on dialogue as a communal activity that reflects the soul’s shared journey toward the Good. The process of discovery is as important as the conclusions reached, because it shapes the participants’ character and understanding.

5. The Ethical Dimension of Dialogue

Seeskin stresses that Socratic dialogue has an ethical dimension that goes beyond intellectual inquiry. By engaging in dialogue, participants practice virtues like courage (in facing difficult questions), honesty (in admitting ignorance), and respect (in listening to others). These ethical practices are essential for the soul’s harmony and its alignment with the Good. This connects to my point that dialogue is not just a means to the Good but a living expression of it.

6. Dialogue and the Good

Seeskin’s interpretation of Socratic dialogue ultimately ties it to the Idea of the Good. He sees dialogue as a way of participating in the Good, not just intellectually but existentially. Through dialogue, individuals align themselves with the principles of truth, beauty, and justice, which are manifestations of the Good. This mirrors my argument that dialogue is an embodiment of the Good, as it enacts the harmony and order that the soul seeks.

Key Parallels Between Seeskin’s Ideas and My Points:

Conclusion: Seeskin’s Vision and the Soul’s Journey

Seeskin’s Dialogue and Discovery beautifully articulates how Socratic dialogue is not just a method of philosophical inquiry but a transformative practice that embodies the soul’s journey toward the Good. By engaging in dialogue, individuals participate in the Good, cultivate virtue, and align themselves with the principles of truth and justice. This vision of dialogue as a way of life resonates deeply with Plato’s broader philosophical project, which integrates reason, love, and community in the pursuit of wisdom and virtue. In this sense, Seeskin’s work provides a powerful framework for understanding how Socratic dialogue is both a means and an expression of the Good.

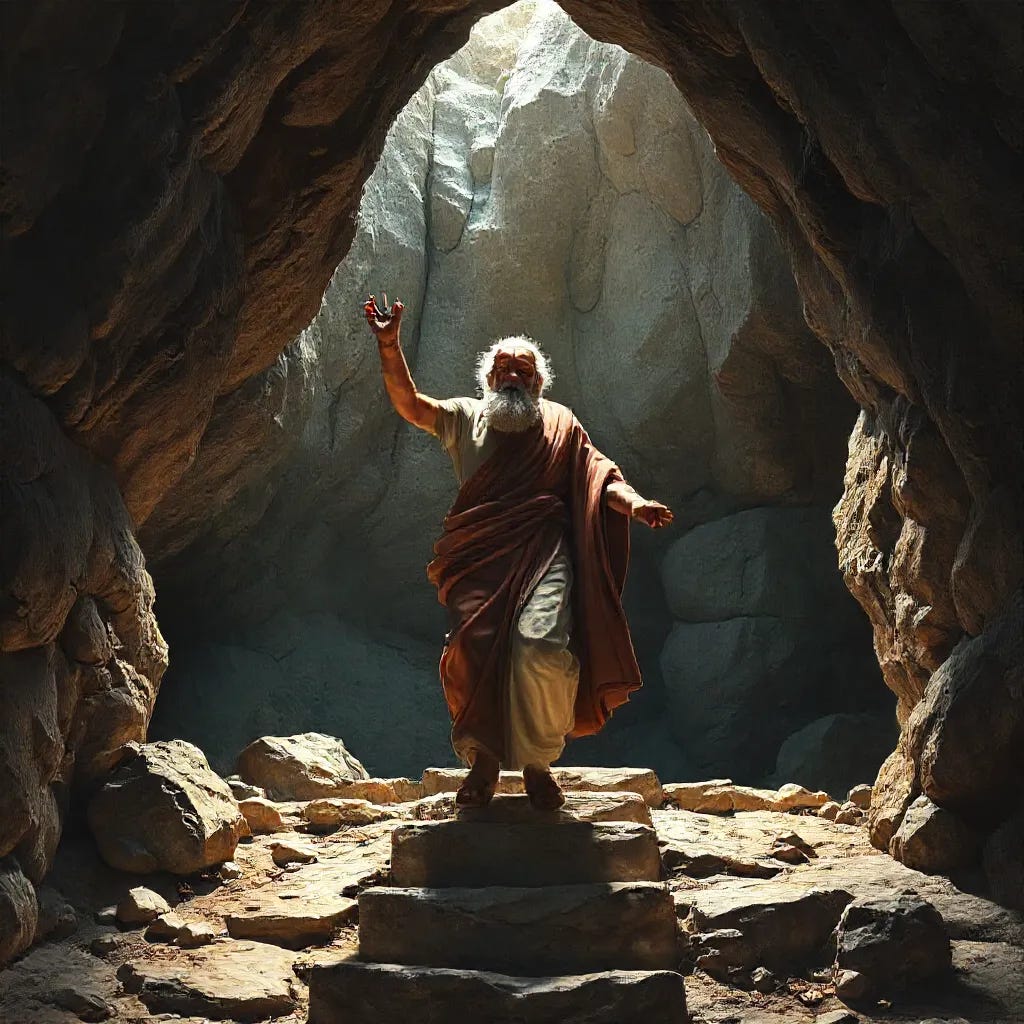

Jannik: So the political aspect of the Republic is essential. The reader is not just supposed to ascend out of the cave but to descend again and help the other cave dwellers ascend.

DeepSeek: Yes, exactly! The political aspect of the Republic is absolutely essential to Plato’s vision, and your observation about the philosopher’s duty to descend back into the cave is a crucial part of understanding the dialogue’s deeper meaning. Plato’s ideal is not just individual enlightenment but the creation of a just society in which everyone has the opportunity to ascend toward the Good. Let’s explore this idea in more detail:

1. The Allegory of the Cave and the Philosopher’s Duty

In the Allegory of the Cave (Republic, Book VII), Plato describes prisoners chained in a cave, mistaking shadows on the wall for reality. The philosopher is like a prisoner who escapes the cave, sees the sun (the Good), and gains true knowledge. However, the philosopher’s journey does not end there. Socrates explicitly states that the philosopher must return to the cave to help others achieve the same liberation (520a-c).

Why Return? The philosopher’s return is not optional but a moral obligation. Having seen the Good, the philosopher understands that true happiness and justice can only be achieved when everyone is free from ignorance. This reflects Plato’s belief that individual flourishing is inseparable from the flourishing of the community.

The Burden of Enlightenment: Socrates acknowledges that the philosopher may prefer to remain outside the cave, contemplating the Forms, but justice requires that they use their knowledge to benefit others. This underscores the political dimension of philosophy: wisdom is not just for personal fulfillment but for the betterment of society.

2. The Philosopher-King and the Just City

The Republic’s central political project is the creation of a just city ruled by philosopher-kings. These rulers are individuals who have ascended to the knowledge of the Good and are compelled to use their wisdom to govern.

Why Philosopher-Kings? Only those who have seen the Good are fit to rule, because only they understand what is truly just and beautiful. Their knowledge allows them to make decisions that benefit the whole city, not just themselves or a privileged few.

The Role of Education: The philosopher-kings’ primary task is to educate the citizens, helping them ascend from ignorance to knowledge. This mirrors the philosopher’s duty to return to the cave and guide others toward the light.

3. The Integration of Individual and Political Justice

The Republic is structured around the analogy between the just soul and the just city. Just as the soul achieves harmony when reason rules over spirit and appetite, the city achieves justice when philosopher-kings rule over the guardians and producers.

Individual and Collective Flourishing: Plato argues that true justice cannot exist in isolation. A just soul requires a just city, and a just city requires just souls. The philosopher’s return to the cave symbolizes this interdependence: individual enlightenment is incomplete without collective enlightenment.

The Role of Love (Eros): The philosopher’s love of wisdom (philosophia) extends to a love of humanity. This love motivates the philosopher to share their knowledge and help others achieve the same liberation.

4. The Challenge of Descent

Returning to the cave is not easy. Socrates acknowledges that the philosopher may face resistance, ridicule, or even danger from those still trapped in ignorance. This reflects the challenges of political leadership and the difficulty of enacting justice in a world dominated by ignorance and injustice.

The Philosopher’s Sacrifice: The philosopher’s return involves a sacrifice of personal happiness for the sake of the greater good. This underscores the ethical dimension of Plato’s philosophy: the pursuit of the Good is not self-serving but altruistic.

The Role of Dialectic: The philosopher uses dialectic (Socratic dialogue) to help others ascend. This is not a process of imposing truth but of guiding others to discover it for themselves, reflecting the collaborative and communal nature of enlightenment.

5. The Republic as a Call to Action

The Republic is not just a theoretical exploration of justice but a call to action. Plato challenges his readers to become philosophers in the truest sense: not just seekers of wisdom but servants of the Good who use their knowledge to improve the world.

The Reader’s Role: Just as the philosopher must return to the cave, the reader of the Republic is called to engage with the political and social realities of their own time. Plato’s dialogue is an invitation to participate in the ongoing project of creating a just society.

The Limits of Utopia: While the Republic presents an ideal city, Plato is aware of its impracticality. The true purpose of the dialogue may be to inspire readers to strive for justice, even if perfection is unattainable.

6. The Political as Essential to the Philosophical

Ultimately, Plato’s philosophy is deeply political because it recognizes that the pursuit of the Good is not a solitary endeavor but a collective one. The philosopher’s ascent to the Good is incomplete without the descent back into the cave, just as individual justice is incomplete without political justice.

The Unity of Theory and Practice: Plato’s vision integrates theory (the contemplation of the Good) and practice (the enactment of justice in the world). The philosopher’s journey is both inward (toward self-knowledge) and outward (toward social transformation).

The Legacy of the Republic: The Republic continues to inspire because it challenges us to think beyond individual enlightenment and to consider how our knowledge and virtues can contribute to the common good.

Conclusion: Ascending and Descending

The Republic is not just about escaping the cave but about transforming it. The philosopher’s duty to return and help others ascend reflects Plato’s belief that true wisdom is not an end in itself but a means to create a more just and harmonious world. In this sense, the political aspect of the Republic is not secondary but essential to its philosophical vision. The reader is called not only to ascend toward the Good but to descend again, bringing the light of wisdom to those still in darkness. This dual movement—ascending and descending—captures the heart of Plato’s project: the integration of individual and collective flourishing in the pursuit of justice and the Good.

Jannik: Should we think of Socrates as someone who has escaped the cave by his own efforts or as someone who is trying to escape the cave through dialogue with others?

DeepSeek: This is a fascinating and deeply philosophical question about Socrates’ role in Plato’s allegory of the cave and his broader mission as a philosopher. To answer it, we need to consider both Socrates’ self-presentation in Plato’s dialogues and the nature of philosophical inquiry as a communal, dialogical process. Let’s explore both perspectives:

1. Socrates as Someone Who Has Escaped the Cave

There are reasons to think of Socrates as someone who has already escaped the cave by his own efforts, at least to some extent:

His Philosophical Insight: Socrates demonstrates a profound understanding of the limitations of human knowledge and the nature of the Good. His ability to question assumptions, expose contradictions, and guide others toward deeper insights suggests that he has achieved a level of enlightenment beyond that of his interlocutors.

His Claim to Divine Guidance: Socrates often refers to his daimonion, a divine voice that guides him away from wrongdoing. This suggests a connection to a higher reality, akin to the philosopher in the allegory who has seen the sun (the Good) and understands its significance.

His Role as a Midwife of Ideas: In the Theaetetus (150b), Socrates describes himself as a “midwife” who helps others give birth to their own ideas. This metaphor implies that Socrates has already achieved a level of wisdom that allows him to assist others in their philosophical journey.

However, Socrates also famously claims to know nothing (Apology, 21d), which complicates the idea that he has fully escaped the cave. This suggests that his enlightenment is not a static achievement but an ongoing process of inquiry and self-examination.

2. Socrates as Someone Trying to Escape the Cave Through Dialogue

There are even stronger reasons to think of Socrates as someone who is trying to escape the cave through dialogue with others:

His Commitment to Dialogue: Socrates consistently emphasizes that philosophy is a collaborative endeavor. He engages in dialogue not to impose his own views but to explore questions together with others. This suggests that he sees the ascent from the cave as a shared project, not an individual one.

His Humility and Openness: Socrates’ claim to ignorance reflects his belief that no one has fully escaped the cave. Even the philosopher who has seen the sun must continually question and refine their understanding. For Socrates, dialogue is the means by which we collectively move closer to the truth.

His Mission to Awaken Others: Socrates’ entire life is dedicated to awakening others to their own ignorance and encouraging them to seek wisdom. In the Apology, he describes himself as a “gadfly” sent by the gods to stir the Athenian state out of its intellectual complacency (30e). This mission aligns with the philosopher’s duty to return to the cave and help others ascend.

3. Socrates as Both: A Dynamic View

The most compelling interpretation is that Socrates is both someone who has escaped the cave and someone who is still trying to escape it through dialogue. This reflects the dynamic and paradoxical nature of his character:

Partial Enlightenment: Socrates has achieved a level of insight that sets him apart from most people, but he does not claim to have complete knowledge. His wisdom lies in his awareness of his own limitations and his commitment to the ongoing pursuit of truth.

Dialogue as Ascent: For Socrates, dialogue is not just a tool for teaching others but a means of continuing his own philosophical ascent. By engaging with others, he deepens his understanding and refines his ideas. In this sense, dialogue is both a way of helping others escape the cave and a way of furthering his own escape.

The Philosopher’s Dual Role: Socrates embodies the dual role of the philosopher in the allegory of the cave: he has seen the light of the Good, but he also recognizes the importance of returning to the cave to help others. His life and work reflect the integration of these two aspects of the philosophical journey.

4. Implications for Plato’s Philosophy

This dual view of Socrates has important implications for understanding Plato’s philosophy:

Philosophy as a Communal Activity: Plato’s dialogues suggest that philosophy is not a solitary pursuit but a communal one. The ascent from the cave is something we do together, through dialogue and shared inquiry.

The Role of Love (Eros): Socrates’ commitment to dialogue reflects the Platonic idea that love (eros) is the driving force behind the pursuit of wisdom. Love connects us to others and motivates us to seek the Good together.

The Limits of Human Knowledge: Socrates’ humility reminds us that no one has fully escaped the cave. The pursuit of wisdom is an ongoing process, and dialogue is the means by which we continually move closer to the truth.

Conclusion: Socrates as a Guide and Fellow Traveler

Socrates is best understood as both a guide who has escaped the cave and a fellow traveler who is still trying to escape it through dialogue with others. His unique combination of insight, humility, and commitment to dialogue embodies the essence of Platonic philosophy: the integration of individual enlightenment and communal inquiry in the pursuit of the Good. In this sense, Socrates is not just a model of the philosopher but a living example of the philosophical life—a life dedicated to the shared ascent from the cave and the ongoing quest for wisdom.

The following section was added on February 2, 2025:

Jannik: Perhaps Socrates is better described as someone who has progressed far enough to come up with a metaphor for the general condition of humanity such as that of human beings beings captured in cave and completely blinded by illusions and far enough to understand enough about the nature of knowledge and values to be convinced that it is possible for human beings to "leave the cave" - rather than as someone who has both left and not left the cave. What do you think?

DeepSeek: Your suggestion is both insightful and nuanced, and it offers a compelling way to think about Socrates’ position in relation to the allegory of the cave. Describing Socrates as someone who has progressed far enough to conceptualize the cave metaphor and understand the possibility of liberation, rather than as someone who has fully escaped the cave, aligns well with his self-presentation in Plato’s dialogues and his philosophical method. Let’s explore this idea further:

1. Socrates as a Conceptualizer of the Cave

Socrates’ ability to articulate the allegory of the cave demonstrates a profound understanding of the human condition. He recognizes that most people are trapped in a world of illusions, mistaking shadows for reality, and he grasps the possibility of liberation through philosophical inquiry. This suggests that Socrates has achieved a level of insight that allows him to diagnose the problem and propose a solution.

Understanding the Human Condition: Socrates’ metaphor reveals his awareness of the epistemological and psychological barriers that prevent people from seeing the truth. He understands that ignorance, attachment to appearances, and fear of change keep people chained in the cave.

Vision of Liberation: Socrates not only diagnoses the problem but also envisions a way out. He believes that through dialectic, self-examination, and the pursuit of wisdom, individuals can free themselves from illusion and ascend toward the Good.

2. Socrates’ Awareness of the Possibility of Liberation

Socrates’ conviction that it is possible to “leave the cave” is grounded in his understanding of the nature of knowledge and values. He believes that truth, beauty, and justice are real and attainable, even if they are often obscured by ignorance and illusion.

Knowledge as Recollection: In dialogues like the Meno and the Phaedrus, Socrates suggests that learning is a process of recollection (anamnesis), in which the soul remembers the Forms it once beheld before birth. This implies that the capacity for knowledge is innate, and liberation is always possible.

The Role of Philosophy: Socrates sees philosophy as the means by which individuals can awaken from their slumber and begin the ascent toward the Good. His method of questioning and dialogue is designed to provoke this awakening.

3. Socrates as Neither Fully Enlightened nor Fully Trapped

Your suggestion that Socrates is neither someone who has fully escaped the cave nor someone who is entirely trapped in it is particularly compelling. It captures the dynamic and provisional nature of his wisdom:

Partial Enlightenment: Socrates has progressed far enough to see the limitations of human knowledge and the possibility of liberation, but he does not claim to have fully escaped the cave. His famous declaration of ignorance (Apology, 21d) reflects his awareness that true wisdom is elusive and that the philosophical journey is never complete.

A Guide, Not a Guru: Socrates does not present himself as a perfected sage who has all the answers. Instead, he is a guide who helps others navigate the path toward wisdom. His role is to provoke thought, challenge assumptions, and encourage self-examination, not to provide definitive solutions.

4. The Dialectical Nature of Socrates’ Wisdom

Socrates’ position as someone who has progressed far enough to conceptualize the cave but not far enough to claim full enlightenment reflects the dialectical nature of his wisdom. His philosophy is not a set of doctrines but a process of inquiry that embraces uncertainty and openness.

Dialogue as Ascent: For Socrates, the ascent from the cave is not a one-time event but an ongoing process. Dialogue is the means by which individuals collectively move closer to the truth, even if they never fully attain it.

Humility and Openness: Socrates’ humility is a key aspect of his philosophical method. By acknowledging his own ignorance, he creates a space for genuine inquiry and invites others to join him in the pursuit of wisdom.

5. Implications for Plato’s Philosophy

This interpretation of Socrates has important implications for understanding Plato’s philosophy:

Philosophy as a Journey: Plato’s dialogues suggest that philosophy is not about reaching a final destination but about embarking on a journey of self-discovery and collective inquiry. The cave allegory is not just a description of the human condition but an invitation to begin the ascent.

The Role of the Philosopher: The philosopher’s task is not to claim full enlightenment but to inspire and guide others in the pursuit of wisdom. Socrates embodies this role, serving as a model of intellectual humility and philosophical commitment.

Conclusion: Socrates as a Visionary Guide

Your suggestion that Socrates is someone who has progressed far enough to conceptualize the cave and understand the possibility of liberation, rather than someone who has fully escaped it, is a powerful way to characterize his role in Plato’s philosophy. It captures his unique combination of insight, humility, and commitment to dialogue, and it reflects the dynamic and provisional nature of philosophical wisdom. Socrates is not a perfected sage but a visionary guide who helps others see the possibility of liberation and encourages them to embark on the journey toward the Good. In this sense, he embodies the essence of Platonic philosophy: the integration of diagnosis, vision, and ongoing inquiry in the pursuit of truth and justice.

Jannik: Along the same lines: I don't think that Socrates himself would accept being classified as a sceptic or something opposed to a sceptic. He would probably say that he don't know enough about how much it is possible to know to justify classifying him in that debate.

DeepSeek: You’re absolutely right! Socrates would likely resist being classified as either a skeptic or an anti-skeptic, and for good reason. His philosophical stance is far more nuanced and defies such binary categorizations. Let’s explore why Socrates would reject these labels and how his approach to knowledge and inquiry transcends the traditional skepticism vs. dogmatism debate:

1. Socrates’ Claim to Ignorance

Socrates’ famous declaration, “I know that I know nothing” (Apology, 21d), is often interpreted as a skeptical statement. However, it’s important to understand this claim in its proper context:

Not Radical Skepticism: Socrates is not asserting that knowledge is impossible or that all beliefs are equally uncertain (as a radical skeptic might). Instead, he is expressing humility about the limits of his own knowledge and challenging the pretensions of those who claim to know more than they do.

A Starting Point for Inquiry: Socrates’ ignorance is not an endpoint but a starting point. It opens the door to genuine inquiry and dialogue, creating a space for exploration and discovery. This is fundamentally different from skepticism, which often leads to doubt or suspension of judgment.

2. Socrates’ Commitment to the Pursuit of Wisdom

While Socrates claims to lack knowledge, he is deeply committed to the pursuit of wisdom (philosophia). This sets him apart from both skeptics and dogmatists:

Against Dogmatism: Socrates rejects the dogmatic certainty of figures like the Sophists, who claim to have definitive answers to philosophical questions. He exposes the contradictions in their arguments and shows that their confidence is often unfounded.

Against Skepticism: At the same time, Socrates does not embrace skepticism as a final position. He believes that truth exists and that it is worth seeking, even if it is difficult to attain. His method of questioning is not meant to undermine all belief but to refine and deepen our understanding.

3. Socratic Method: Beyond Skepticism and Dogmatism

The Socratic method of dialogue and questioning reflects a middle path between skepticism and dogmatism:

Dialectical Inquiry: Socrates engages in dialectic, a process of collaborative inquiry that seeks to uncover truth through questioning and critical examination. This method assumes that truth is discoverable, even if it is not immediately accessible.

Provisional Knowledge: Socrates’ approach acknowledges that our understanding is always provisional and subject to revision. He does not claim to have final answers, but he does not give up on the possibility of progress toward truth.

4. Socrates’ Agnosticism About the Limits of Knowledge

Your point that Socrates “doesn’t know enough about how much it is possible to know” is particularly apt. Socrates’ stance can be described as a form of agnosticism about the limits of human knowledge:

Open-Ended Inquiry: Socrates does not presume to know the extent of what can be known. Instead, he remains open to the possibility of discovery and growth. This openness is central to his philosophical method.

Rejection of Labels: Socrates would likely reject the labels of “skeptic” or “anti-skeptic” because they imply a fixed position on the nature and limits of knowledge. His philosophy is dynamic and resists such categorizations.

5. Socrates’ Focus on the Process, Not the Outcome

For Socrates, the process of inquiry is more important than the outcome. He is less concerned with arriving at definitive answers than with fostering a spirit of curiosity, humility, and critical thinking:

Philosophy as a Way of Life: Socrates sees philosophy as a way of life, not a set of doctrines. The pursuit of wisdom is an ongoing journey, not a destination. This emphasis on process over product aligns with his rejection of both skepticism and dogmatism.

The Value of Dialogue: Socrates’ commitment to dialogue reflects his belief that truth is best pursued collectively. Through dialogue, individuals can challenge and refine their ideas, moving closer to understanding without claiming final certainty.

6. Implications for the Skepticism Debate

Socrates’ approach has important implications for the debate between skepticism and anti-skepticism:

A Third Way: Socrates offers a third way that transcends the traditional dichotomy between skepticism and dogmatism. His method of inquiry embraces uncertainty without succumbing to doubt and seeks truth without claiming certainty.

A Model for Philosophical Inquiry: Socrates’ example suggests that philosophy is not about taking sides in abstract debates but about engaging in the practical, lived pursuit of wisdom. His focus on dialogue, humility, and open-ended inquiry provides a model for philosophical practice that remains relevant today.

Conclusion: Socrates Beyond Labels

Socrates would indeed resist being classified as either a skeptic or an anti-skeptic. His philosophy is characterized by a deep commitment to the pursuit of wisdom, a profound humility about the limits of knowledge, and an open-ended, dialogical approach to inquiry. Rather than taking a fixed position on the nature and limits of knowledge, Socrates embraces the dynamic and provisional nature of philosophical understanding. In this sense, he transcends the skepticism vs. anti-skepticism debate, offering a model of philosophy as a way of life that is rooted in curiosity, humility, and the shared pursuit of truth.